For the first time in the history of European Go, the European Go Federation has published a yearbook. The 2016 European Go Yearbook counts no less than 576 pages and reports on the biggest and most prestigious European go happenings of the year. Amongst other things, it features interviews with the new European professionals Artem Kachanovskyi 1p and Antti Törmänen 1p, an extensive chapter on 41 countries and their national championships, descriptions and beautiful photos of major European go events, and 80 pages on AlphaGo and the rise of Artificial Intelligence in our sport. Throughout the book, a total of 200 game records accompany the stories, of which many have been reviewed by top European players.

The book was officially released in July at the European Go Congress in Oberhof, and has received praise from the go community ever since. We caught up with the author, Kim Ouweleen 4d from the Netherlands, in an interview. The following questions have been collected by Antonius Claasen from go players all over the world.

Hello Kim, thank you for your time. Could you introduce yourself to the reader?

Kim: Hello, thank you for having me. My name is Kim Ouweleen, I'm 29 years old and was born and raised in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. I have a Master's degree in art history and also make art and illustrations myself (see here). I enjoy writing as well: I am in the News Team of the EGF and have previously written an art book about Belgian painter and cartoonist Kamagurka, which will be published by Uitgeverij Waanders in 2018. And of course I'm an enthusiastic go player. Since 2011, when I hosted the video show Murugandi Reviews for EuroGoTV, I started teaching go actively. In 2012 I launched BadukMovies with Peter Brouwer, for which we created new go tutorials every week until July 2015.

When and how did you start to play go? Who was your first teacher and what is your level at the moment?

- Antonius Claasen, the Netherlands

Kim: I started playing go in September 2004, when I was almost 16 years old. I discovered the game thanks to my parents, who had a go set tucked away in a corner where we kept our board games. The box was grey, with patterns of black and white circles on it and "GO" written in red capitals, accompanied by Japanese characters. In its simplicity the box looked underwhelming, but when I asked my parents about the game they told me it was Asian and "very difficult". After asking more questions, it turned out that my mom had once bought the game for my dad, as a present he might enjoy as a mathematics teacher. They had never actually played it.

So one day I convinced my dad to go through the rules together and play a few games. We had no idea what we were doing, but decided that I had won, and my curiosity was triggered. I don't remember if it was that same day, but I soon looked for a place to play go online and found the Kiseido Go Server. There I lost all my games miserably. I almost gave up on the game, but the fact that I couldn't stand losing kept me going. I told myself that I would play until I finally won a game, and then quit. That plan failed. From the moment I won my first game of go, I was hooked.

I guess my first go teacher was KGS. The server allowed me to play obsessively in the first few weeks, which soon turned into months. In those days I used every resource I could find to try and improve my knowledge of the game, which was practically non-existent. I didn't know about go books, tsumego problems or Sensei's Library, so I relentlessly pestered my opponents for advice and regularly started desperate chat conversations with random KGS strangers for help. I played go during school breaks and in the evening when I was at home. By playing constantly, I improved steadily. I think it was around the time that I reached the 1 kyu mark that I switched to playing blitz games, and only blitz. It allowed me to play even more, recognise recurring patterns in my games and change them when necessary.

My first personal teacher was Yan An 7p, under whom I studied go in 2010 in Wuhan, China, for three months. I heard about his international go school through Guo Juan 5p, and found myself in an apartment in Wuhan not too long afterwards, with two other Dutch go players, a German and a Frenchman. Each morning we played simultaneous games against Yan An, who reviewed our matches in Chinese and broken English. During the day we competed against each other and made futile attempts to force ourselves on tsumego problems. In the weekends we would visit Yan An's two go schools, where we played against kids aged 5 to 10. We took part in the dan classes, where the strongest kids were 6 dan. Studying go in China and losing almost all my games against Yan An, took me back to the feeling I had when I had just started playing on KGS. I learned how tough go can be and at the same time how satisfying it can be when you finally win that 1 game out of 10. There, I also got my first glimpses of what it is like for the kids that aspire to become go professionals. More than anything, my trip to China brought me in touch with the cultural and sportive aspects of go.

My level has been 4 dan for a while. The stronger you become in go, the more difficult it gets to improve. Lately I have regained my enthusiasm for playing and the struggle to get better, and I'm looking forward to playing more tournaments.

How did go change your life?

- Antonius Claasen, the Netherlands

Kim: When you look back at it, it's very strange how such a small thing can have such a big impact on your life. If my mom had never bought that go set for my dad, and if I then had not gone on to find KGS on the Internet and stick with the game just long enough to start appreciating it, my life would look a lot different. Today, most of my friends are go players, a big chunk of my time and of my working life involves go. I have traveled all over Europe for go and have been to tournaments in China, Japan and South Korea. Without go, I would never have met Justyna, who I've been together with for 6 years now. It's a strange thing, how one can discover a micro cosmos among the billions of micro cosmoses in the world, and become part of it to the point that it becomes a part of you.

How did the process of the 2016 European Go Yearbook start?

- Pavol Lisý, Slovakia

Kim: In early 2016, I became a member of the News Team of the European Go Federation, which means I started writing online news articles about go happenings in Europe. Sometime in September, during one of the Skype meetings of the team, Lorenz Trippel (secretary of the EGF) announced that the EGF was thinking about a yearbook. I wasn't actually at the meeting, but I later found out that my name had been put forward (thank you, Laura) as a good fit for the task. I decided to write a proposal to the board of the EGF, with my views on and approach to a possible European Go Yearbook. My proposal was answered with enthusiasm and the rest is history.

576 pages is quite something. How much time did it take you to write the yearbook and what was your biggest challenge?

- Cornel Burzo, Romania & Marika Dubiel, Poland

Kim: I started working on the yearbook in December 2016 and could focus all my time and energy on it from the start of the new year. I expected to work on the book full-time for about three months, but eventually it took me the better part of half a year. Luckily, I wasn't completely alone and could count on the support of Lorenz Trippel and Pavol Lisý during the project. They helped me with details when necessary, so I could focus on what was most important. Even though I had their backing, it was up to me to create about 90% of the content from scratch, which at times seemed like an insurmountable task.

There were many obstacles along the way. For starters, the fact that this was the first ever yearbook of European go necessitated proper introductions to every chapter and sub-chapter in order to create a solid background for the reader. It’s one of the main reasons that the book has so many pages. Another obstacle at the start of the process was finding out how to create go diagrams and present them in an aesthetically pleasing way, which was new to me. It didn't take me long to get the go diagrams figured out in GOWrite and the work became routine. However, only after I had already done quite a few chapters, the designer of the book told me he needed the diagrams in a different file format than .PNG. The diagrams had to be vector graphics, so they could be rescaled without losing quality. It was something I hadn't realised at all, so I needed to redo all the diagrams.

These are the kinds of mistakes that you learn from along the way and are relatively easy to fix. I would say that the biggest issues during the writing process were the gathering of information and the communication with foreign go players.

In order to start writing, I first had to collect all the material to work with, which was very time consuming. Everything had to be done rather hurriedly, because a yearbook is interesting for the public within a limited timeframe. I had to create an extensive checklist for myself to keep track of the information I still needed for various chapters and which people I could approach on these matters. This resulted in endless streams of E-mails and Facebook messages with go players from all over Europe and beyond. The communication with organisers and go players involved was crucial, and was either very rewarding or a real struggle. Often it was difficult to find the right person. Then, even if the person was found, it was sometimes a challenge to get a hold of them.

As a writer, you need some interesting information to create a story; it is impossible to create an anecdote about a tournament from "These were the winners: 1. Ali Jabarin 2. Pavol Lisý 3. Mateusz Surma". Thankfully, many go players responded to my queries enthusiastically and were usually very helpful. It was rewarding to finally find the photos of a certain tournament, or get an E-mail response from a champion of a country. I was also pleasantly surprised with the commitment of many top European players, who agreed to help and created wonderful game reviews.

A great example of a moment of triumph was when I accidentally stumbled upon a Facebook page about go in Ohrid, Macedonia. There were some beautiful photos on the page, of a go board filled with stones and a stunning summer lake in the background. I double checked, but Macedonia was not yet recognised as an EGF country. As it turned out, Filip Paskali, a go player from Ohrid, had organised the first ever go tournament in Macedonia in 2016. He had taught the game to his friends and started a local go club. I interviewed Filip for the book and wrote a small chapter on Macedonia. After I finished the yearbook, the EGF included Macedonia on their website. My girlfriend and I later visited Filip and his girlfriend Elena in Ohrid, and played a game of Pair Go at the Ohrid lake.

An interesting example of difficult communication that resulted in success, were my attempts to approach the Azerbaijani go community. After many hours of asking around and searching, I had finally found some people to talk to, but it turned out they only spoke Azerbaijani and Russian. Luckily, we live in the age of technology and with the usage of Google Translate and an Azerbaijani translating program, I talked to Bahadur Tahirbayov, the Azerbaijani champion. This resulted in one of the better interviews in the book.

How did you manage to collect reports on so many countries, including many personal messages of the national champions? Was it difficult to get good feedback and how difficult was it to get connected to the right people?

- Lorenz Trippel, Switzerland

Kim: This really depended on the country. The first thing I did was to send out E-mails to all the national associations with a cry for help. Sadly, the responses were minimal and as I continued, I learned that personal contact (one on one) goes a long way.

For many of the "big countries" in the European go scene, such as Germany, France, the Czech Republic and Russia, it was easy to gather information. I often relied on go friends or acquaintances that live in the different countries, and made use of their talents and connections to get to the right people or information. For the less known go countries, I had to be more resourceful; I asked around if anybody knew go players from, say, Latvia, Kazakhstan or Bosnia, and when these attempts were fruitless I discovered that the websites of the European Go Database and the Pandanet Go European Team Championship could sometimes provide new names. Facebook was always crucial in the last stages of tracking people down and starting a conversation.

Which countries did you omit? Why are there no reports fom Greenland or Malta?

- Lorenz Trippel, Switzerland

Kim: During the writing process of the chapter National Championships, I came across countries that didn't organise tournaments to determine a national champion. At first I considered leaving these countries out of the book altogether, but then I realised this would be a pity and created an additional section Countries without National Championships at the end of the chapter.

For the selection of the countries, I used the website of the EGF as a starting point, which gave me a list of recognised countries, lapsed countries and observer members. The countries that are official members of the European Go Federation pay a yearly fee to stay in the inner circle and reap its benefits. "Lapsed countries" are countries that used to be official members in the past, but no longer are. "Observer members" are countries such as South Africa, that are not part of Europe, but show interest in and are "observing" the European go scene.

During the gathering and writing process, I came across countries like Macedonia, which were not even mentioned on the website of the EGF. I was unsure which countries to include and which to leave out, but in the end I decided to simply include information on every country I could find, with the sole criterion that there had been any go activity in the country worth mentioning. Based on this requirement, I decided to exclude Luxembourg, as Luxembourgian go players I spoke to told me that nothing had been organised in the country in 2016. The same applied to Bulgaria, but that country had one young and upcoming go player, Sinan Djepov 5d, who I decided to do an interview with and asked for a commentary on one of his best games. Some other countries simply proved impossible to contact, or are unknown to have any go community whatsoever, and were left out for those reasons. These included: Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Greenland, Kosovo, Liechtenstein, Malta, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, San Marino and Vatican City State. If you are a go player from or living in one of these countries, please contact us!

What is your favourite match in the yearbook and why?

- Matthew Mennie, Canada

Kim: Good question. It's difficult to pick one, as there are so many worth mentioning. It also depends on the criteria I choose by. I worked together with many of the top European players, and I really appreciate their efforts for the book. Some of them went the extra mile, such as Lukáš Podpěra 7d, who did an extensive commentary on the match he played for third place in the European Championship, against Mateusz Surma 1p (game 125). Others, like Pavol Lisý 1p, Alexandre Dinerchtein 3p, Ali Jabarin 1p and Ilya Shikshin 1p, created multiple game commentaries for different chapters, for which I am also grateful.

In terms of the quality, I feel like the matches played in the 3rd European Professional Qualification Tournament, the 2nd European Grand Slam and the 60th Polymetal European Go Congress, were of a very high level and exciting to watch.

In terms of style I am a fan of Mateusz Surma 1p, who time and time again finds moves I would never have thought of and always comes up with ways to rescue his groups in the most hopelessly looking situations. When he is behind, you know there is always the possibility of a miraculous comeback. I find his matches inspiring. I also enjoy the style of Cristian Pop 7d.

Some of my personal favourites from the book are commentaries for the French Open Championship by Tanguy Le Calvé 6d (game 12 vs. Motoki Noguchi 7d) and Junfu Dai 8d (game 13 vs. Motoki Noguchi 7d).These games are interesting to play through, include some special shape moves and tesujis, and are elegantly explained by the players.

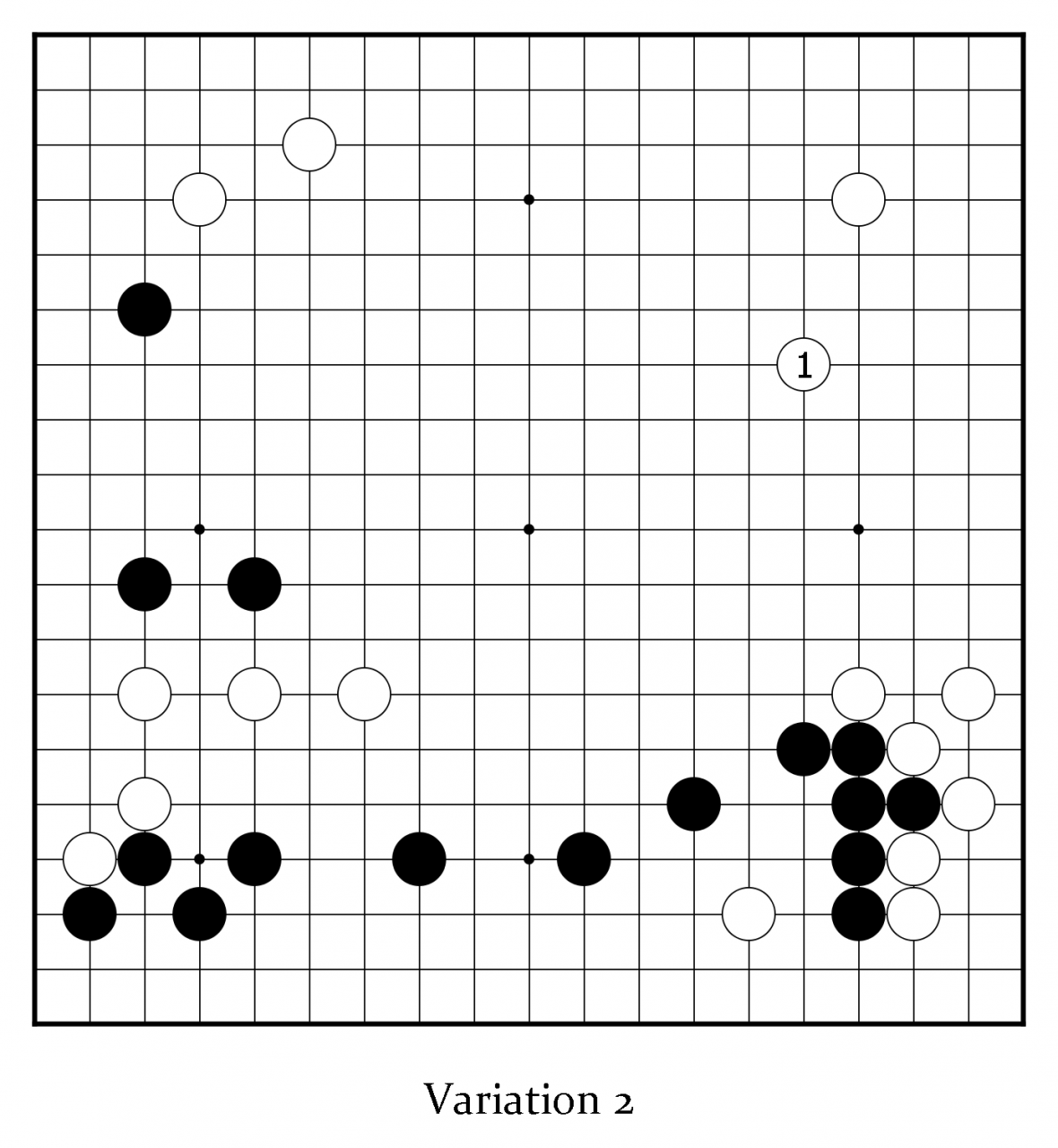

I like funky and unusual moves, so seeing Variation 2 in Game 43 (British Championship, reviewed by Matthew Macfadyen 6d) was like a breath of fresh air.

It was interesting to find out how every country has their own championship system. For example, Finland has a complicated selection procedure for the Finnish Championship. And after the Finnish Championship has been played, there is still no champion, but instead the top two players go through to a best-of-three Final. In 2015 this Finnish Final was played between Juri Kuronen 6d and Juuso Nyyssönen 5d, which the latter barely managed to win by 2 games to 1. This scenario repeated itself in 2016, with the exact same players; the three games they played for the Finnish play-off Finals are all included in the book (games 9-11, without commentary) and were fun to replay, with many ups and downs, strange mistakes and sudden turnarounds.

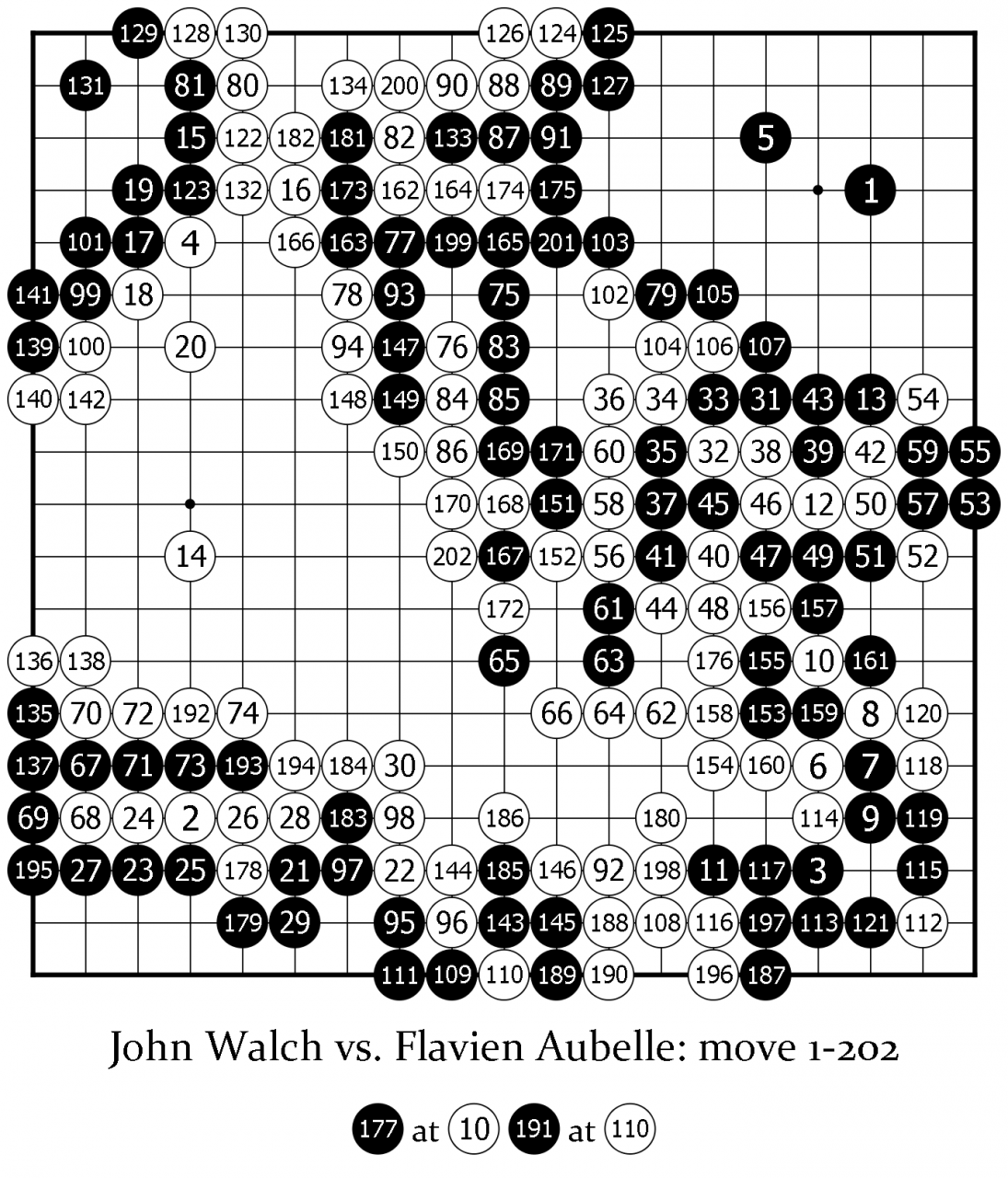

Then there was the tanuki no hara tsuzumi (狸の腹鼓) tesuji that John Walch 4d played in the deciding game for the Swiss championship (game 39); two shocking moves on the first line that you rarely see in important matches.

In terms of eloquence, the commentary by Antti Törmänen 1p of his match against Ogawa Tomoko 6p was the best, and required the least amount of adjusting or correcting (game 1). I am very happy that this game is included in the book, as it gives us a small window into Antti's life in Japan and the level that his go has achieved overseas.

Finally, the games played by AlphaGo (Master) that can be found in the last chapter, were very inspiring for me. They opened my eyes to new possibilities, and made me think twice about joseki and standard patterns; for the first time in a long time I realised that anything is possible in go and that it is perfectly fine and fun to experiment with new and strange-looking moves.

Will there be a yearbook of 2017 next year? And would you be willing to write it?

- Alexandre Dinerchtein, Russia & Li Yue, China

Kim: At this stage, it is unclear if there will be a next edition, but the EGF has expressed interest in continuing the project. I believe the 2016 European Go Yearbook was a success and a next edition would be a great thing for European go. A yearbook bundles the best moments of European go of the year, and showcases a kind of unity of European go throughout all its diversity. In my eyes, such a book is the perfect business card and promotional material for the EGF, whilst at the same time it is an ode to the organisers and enthusiasts throughout the continent that make all these wonderful go events possible.

Although it was a lot of work, I am very happy I persevered and I am proud of the book. If the EGF decides to continue the project, I would definitely consider writing a 2017 edition.

What would you do differently in the next edition?

- Marika Dubiel, Poland

Kim: Another mistake I made this time around, was to design the book while writing it, even though the final form of the book was up to a seperate designer. I had selected all the photos I wanted to include and had prepared each chapter in a seperate file meticulously, basically ready for print.

The work I had put into this was largely for nothing and undone when the book designer transferred the contents into InDesign and changed them around. This resulted in removed images and errors in the transfer of text, which forced me to double and tripple check everything. It gave both me and the designer a huge headache, so this is definitely something I would do differently.

As I mentioned before, in the 2016 edition of the European Go Yearbook it was necessary to include extensive background information on tournaments and their systems. I think the next edition will require less detailed explanations, since the 2016 edition can always be used as a reference. I expect that the 2017 European Go Yearbook would turn out to be much smaller in size, in the range of 250 pages. A thinner yearbook would also mean a broader financial budget for better quality of production - perhaps a hardcover edition, thicker paper, etc. - and a lower price for the customer.

One of my favourite parts of the yearbook are the interviews. I would definitely like to include some in the 2017 edition again, but maybe with a twist - asking different kinds of questions to bring out new aspects of the go community. Something similar has already been done in the Ranka Yearbook of the the International Go Federation, who used to ask players about their day jobs. The topic may on one hand sound banal, but on the other it does give a little insight into the lives of the players.

Thank you very much for this interview!

Kim: Thank you.

If you are interested in purchasing the 2016 European Go Yearbook, you can find three pdf-previews and more information here.

If you have already received your copy, please share your thoughts!