Introduction

A decade ago, the European Go Federation began an exciting journey when they signed a groundbreaking contract with the China-Europe Go Organization (CEGO), a community of go enthusiasts from China. This visionary partnership has since become the catalyst for transformative projects reshaping the European go landscape. Endeavors that once seemed far-fetched, such as a European professional system, the Grand Prix series, the Grand Slam, the EGF Academy, the CEGO program (a half-year scholarship in China for talented European youth) and regular invitations to international professional competitions are all now recurring events and common knowledge. It’s safe to say our accomplishments together mark a pivotal chapter in the history of European go.The original contract was due to end in 2022 but was prolonged for an extra year, bringing this first chapter to a close shortly. I, for one, hope that CEGO’s support will continue!

This article celebrates the ten-year partnership between the EGF and CEGO, divided into three parts. The first features Martin Stiassny, the EGF President, sharing his story of the establishment and evolution of this fruitful collaboration. In the second part, Stanisław Frejlak 1p shares his experience of attending the CEGO programs in China. Finally, I will offer my impressions and insights from a decade as a professional player.

Story of Cooperation – By Martin Stiassny, the EGF President

It all started in 2012. The American Go Association had begun their project of a professional system in cooperation with Korea. Korean pros in the center of Budapest explained to me, however, that Europe had a stronger foundation upon which to build a professional system than what Korea had had when they began their own professional system in the 1950s. At the time, I was very skeptical about a professional system in Europe, but at the 2010 EGC in Tampere, many strong players signed a declaration of interest for a professional system in Europe.

One day I got an e-mail from Li Ting which read, “Martin, what are your expectations and requirements for a European professional system? I am in contact with my Chinese weiqi friends, and they want to help European go.” This message truly caught me by surprise, and I answered Li Ting with, “Financial support, up to €100,000 a year and a commitment for three to five years. Better five.” Li Ting surprised me again with her positive response, “This should be possible!”. Well, anyone who knows me a bit will surely understand my reaction: seize the chance, you never know if you’ll get a second one.

That’s when I learned that it’s quite normal in China to be a part of big friend circles dedicated to a particular topic. Li Ting just so happened to be a member of the weiqi lovers. This is a group of people connected by their love of go, through which they have made lasting relationships. This community of enthusiasts gave rise to CEGO. CEGO is no company, there is no logo or website, and even to this day I am uncertain of its size or the extent of their members’ financial contributions to the organization.

In the middle of 2012, Li Ting and I began designing a collaboration contract. Recognizing the importance of stronger amateurs to fill a future professional system, we thought it important to provide rigorous training for talented European players. This led us to several objectives:

- Improve the strength of amateur European players

- Establish a functioning professional system in Europe

- Encourage organizational support with the EGF

- Enhance the popularity of go and increase its audience in Europe

- Extend existing cultural contacts between Europe and China and develop new ones.

- 12/2012: Signing of the memorandum of understanding for cooperation

- 02/2013: Drafting the final ten-year contract (2013 – 2022)

- 04/2013: Contacting all EGF member countries to secure a positive majority for signing the contract

- 05/2013: Official contract signing (published on the EGF webpage) by Mr. Lyu Bin and myself

- 12/2014: Signing of an additional document formalizing the cooperation with the Ge Yuhong Academy.

Simultaneously, back in Europe, we established the EGF Academy featuring both Chinese and European professionals as online instructors. The creation of the EGF Academy represented a pioneering leap forward in creating a base of strong amateur players from which to pluck our future European pros.

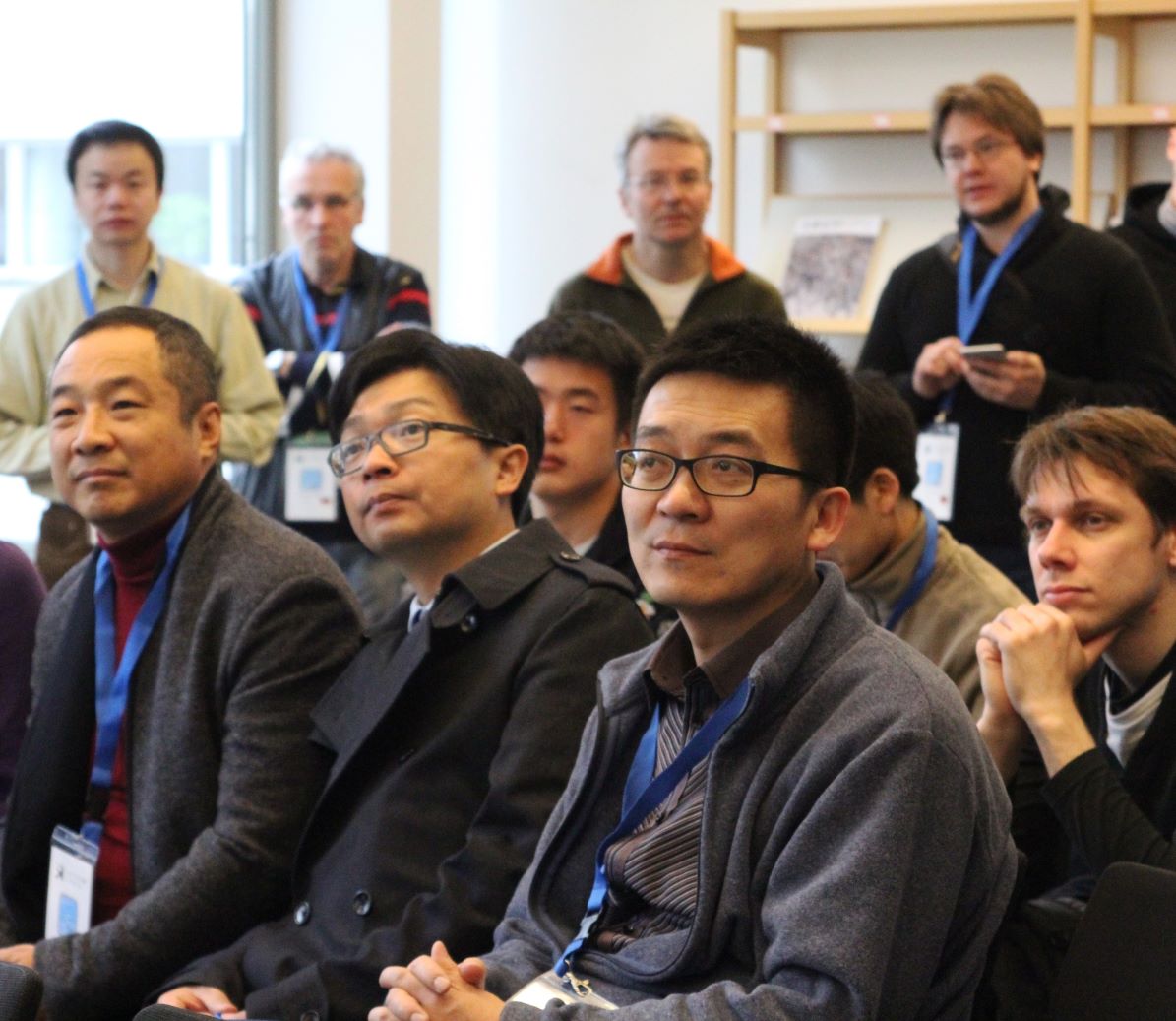

The academy projects were crucial, but the groundwork for our collaboration had already been laid for our Sino-European partnership at the 2nd World Mind Sports Games (WMSG) 2012 in Lille, France. Without written formalities or intricate agreements, cooperation with our CEGO friends for this event was based on simple trust and served as a kind of guideline for the coming years.

The story of CEGO and the 2nd WMSG is a good one that few know. The inaugural 2008 WMSG in Beijing hosted about 600 players for the go portion of the event. The 2nd WMSG was planned for 2012 in Europe. However, due to sponsorship challenges, the event was reconfigured to focus solely on amateurs, which meant there would be no prize money. During an International Go Federation (IGF) Director’s meeting in Guangzhou at the World Amateur Go Championship (WAGC) in 2012, China and Korea announced their decision to withdraw from the amateur-only event. On top of that, the IGF told us it wouldn’t have the funds to support the organizing team, despite Europe’s persistent interest in the 2nd WMSG. The IGF suggested a scaled-down, three-day joke of a tournament. Frustrated, I left the meeting for Beijing and, in collaboration with Li Ting, secured significant sponsorship for the go portion of the 2nd WMSG. This support from CEGO ensured the success of the event, featuring a ten-day tournament with 200 players from around the world. While CEGO is made up of Chinese go enthusiasts, the official Chinese Weiqi Association did not send any players to Lille.

Back to the project: nobody was certain of how our European players would get on in Beijing for six months, but the feedback was positive. It was hard work, six days a week with additional lessons in the Chinese language, participation in local tournaments and extra homework at night.

Over 30 players have improved their game in the Ge Yuhong Academy since the program began. If you check the current EGF rating list, you’ll find that over 80% of the top players have taken part in this training over the past decade. Building this relationship with the Ge Yuhong Academy opened the door for other milestones:

- Start of the professional system in Europe

- Europeans playing in the Silk Road Tournaments

- Participation of a professional European team in the Chinese C-league

- Invitations for European pros to attend important tournaments in China, Japan and Korea

- Increased interest in European go in general.

Under the CEGO-EGF cooperation contract, the Professional Qualification Tournament has used the Chinese rules as a way of popularizing the Chinese system in European tournaments. Now, in 2023, it’s not uncommon to see Chinese rules used at European competitions, including at the European Go Congress.

Interest in strong European players grew in China. This led to the creation of the Silk Road Tournament by the Xi’an Weiqi Association in 2015. Pavol Lisý’s victory marked the first time a European player won a Chinese tournament. The buzz in China was apparent as the EGF began receiving invitations to nominate representatives for international tournaments, solidifying Europe as a fully-fledged member of the international professional go scene. Nowadays one sees regularly on tournament announcements: “open to EGF and AGA professionals”.

From the Chinese perspective, C-league participation by a European team is probably the most significant development. In China there are several leagues for teams of professional players, sponsored by entities representing Chinese cities or big clubs. These team competitions are played on four boards, involve prize money and have face-to-face tournaments. Representatives from Tsinghua University in Beijing, with the collaboration of our CEGO partners, extended this opportunity to a European professional team – an absolute sensation. The EGF could nominate three players, and the Chinese sponsors nominated one EGF pro. The European Professional Championship serves as a qualification for the C-league team. The European team has participated in the C-league three times. COVID interrupted our invitations in recent years, but we anticipate a return in 2024. Special thanks go to Prof. Han Lixin and Mr. Shen Zhengning for their instrumental role in making this unique opportunity possible.

CEGO and EGF collaboration also means more Chinese players attending the European Go Congress and, in 2018, for the first time there were more Chinese than Japanese players in attendance, highlighting the growing connection. The friendly ties extend beyond the goban, even, with a group of five CEGO members visiting me in Leksand on their holiday trip through Scandinavia, led by Mr. Li Gangyi, the president of the Xi’an Zhonge Weiqi Institute and founder of the Silk Road Tournament. A team from Beijing also came to Trier, Germany for some sightseeing and competition against strong German amateurs. This group was led by Prof. You Xiaochuan from Tsinghua University who supported the European pros by allowing them free use of the Golaxy AI program (of which he was co-owner) in 2016 before AI became widely available.

What am I trying to say with all of this? Namely, that CEGO and European go are growing together. Our partnership is based on friendship, respect, relationships and dreams for the future. Our friends would like to see us win more often internationally, of course, and I am sure it will happen sooner or later.

Did you know that the first Chinese Go Congresses were initiated and co-organized by Prof. You, based on his experiences of our EGCs since 2011? With this contract not only have things in Europe developed in a positive direction, but also partly in China.

Let’s dive into the European go scene beyond the professional system. Alongside certifying pros, something had to be done about tournaments across Europe. Our pros needed more than just teaching opportunities to earn money. So, I added a clause in the contract about the European Grand Prix, an old idea from 1986, featuring Grand Slam Tournaments as highlights.

The European Grand Prix kicked off in 2014 as a series of tournaments where players from EGF-member countries could win Bonus Points, similar to series in other sports like tennis or skiing. It wasn’t easy at first to convince tournament organizers to pay the EGF to join the Grand Prix instead of seeking sponsorship, but fast forward to 2023 and the European Grand Prix is well-established, with up to 12 tournaments every year, including the Grand Prix Final Tournament at the end of the season for the most successful Bonus Point holders.

While the Grand Prix and Grand Prix Final did set the stage for a European professional system, it wasn’t altogether enough. In 2015, the first Grand Slam tournament took place in the Chinese Cultural Center in Berlin, featuring 12 players, a mix of professionals and amateurs. The professionals qualified automatically, while the amateurs passed a selection based on the Bonus Points, rating, and a qualification tournament. The winner took home €10,000 – a new benchmark for tournaments in the western go world. As of 2023, we’ve had eight Grand Slam Tournaments, entirely funded by our CEGO friends, including Yike and Quzhou Lanke.

Grand Slam? Yes, I chose this name to evoke the iconic tennis events, hoping for more than one Grand Slam per year. But, I’m sorry to say, we have yet to find additional sponsors for a second, third or fourth Grand Slam in the year. Additional Grand Slams is one of our goals for the future.

Another aspect of the Grand Slam approach: we hoped for a lot of publicity. In 2015, we expected the media (local TV, press) in Berlin to be interested in reporting on our prestigious event. With a purse of €10,000, go must be a top sport, right? But, although our event was promoted by the Chinese Cultural Center, the interest never really appeared. It is still very difficult in Europe to get media attention for go tournaments.

Here’s a short summary of what’s new in 2023 compared to 2012 thanks to the CEGO-EGF cooperation contract:

- A professional system, with European professionals attending international tournaments

- The EGF Academy, an essential tool to forge future European stars

- The European Grand Prix, with the yearly Grand Prix Final

- The new European Professional Championship Tournament

- The Grand Slam, with the largest prize purse in European go

- The international acceptance of Europe and its progress in recent years

- An extended base for spreading go in Europe, for example via Twitch, with many options for the future.

A decade of collaboration – successful despite the challenges posed by the “COVID-years”, which were especially tough on our Chinese friends. Unflinchingly, our Chinese partners, particularly Mr. Lyu Bin, the president of CEGO, upheld every commitment they ever made. I express my gratitude for this wonderful partnership and look forward to negotiating a new agreement for the upcoming years in the coming month.

CEGO Programs – By Stanisław Frejlak, EGF 1-dan Professional

As a part of CEGO’s support for European go, the CEGO program was introduced — a five-month study abroad program at one of the best go schools in China, the Ge Yuhong Go Academy. The program got under way in 2013 and has continued annually ever since. Each year, a select few of the strongest and most promising players from Europe are chosen and awarded a scholarship to pursue their studies at the Academy.

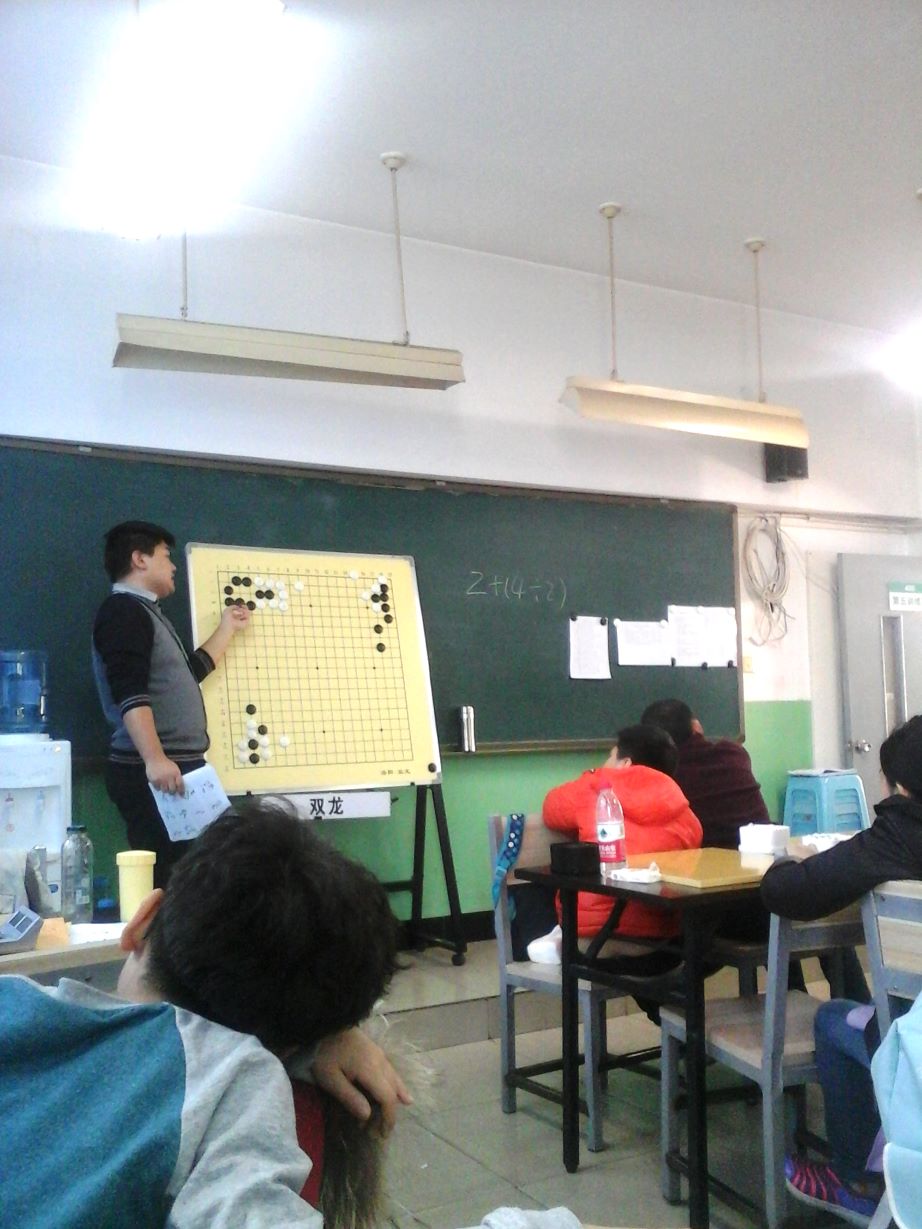

In 2013, a few European players traveled to Beijing for the program’s first edition. They stayed for a few months in a hotel alongside Zhao Baolong 2p, an English-speaking go teacher. They participated in a tournament at the Ge Yuhong Academy called the Big Cycle every month, the results of which assign the Academy students to specific leagues. Subsequently, over the course of a month, the students play with their fellow league members in Small Cycles, striving to ascend to the next league or avoid relegation. However, the European players did not participate in the Small Cycles. Instead, they played with each other and dedicated time to studying under their teacher’s guidance.

From the second year on, CEGO made the strategic decision to integrate the European students into the routine training program at Ge Yuhong Academy. Despite the language barrier, the European students greatly benefited from playing numerous games against diverse opponents in a serious atmosphere. Moreover, the immersive academy environment provided ceaseless motivation to solve life & death problems and study variations. CEGO rented a new apartment every year within the vicinity of the school to be shared by the players from Europe.

Besides training at the Academy, CEGO students had the opportunity to take part in various tournaments in different cities across China, the Silk Road Tournament being the most notable one. These competitions differ from those in Europe as only dan-level players are invited, ensuring a balanced playing field. The tournament format is analogous to the Chinese Pro Qualifications – instead of employing the MacMahon system, a Swiss system is utilized. Tournaments last for a few days, comprising over ten rounds of intense gameplay.

When I first learned about the CEGO program in 2015, I was a freshly minted 5-dan player. I had just finished high school and was very excited by the prospect of traveling to China to study go. I was told that to be accepted the following year, I would need to reach 6-dan. I did it and was accepted to the program alongside two European professionals, Mateusz Surma and Ali Jabarin, Jonas Welticke (another newly minted 6-dan player like myself), and two young stars: Ashe Vázquez and Viacheslav Kaymin.

For the CEGO program in 2016, Ge Yuhong Academy was cooperating with the Ding Lie Academy, another go school located nearby. Between the two schools, there were one hundred pupils split into a number of six-person leagues. The lower leagues played in the Ding Lie Academy building, which we jokingly dubbed “the Kindergarten”. Indeed, the leagues played there were populated by very young kids, and the tables were equipped with corner guards made of sponge.

In contrast, the Ge Yuhong Academy looked more austere. The first leagues consisted of Chinese professional players. Notably, in a corridor leading to the classrooms, there hung over one hundred photographs of students who succeeded in turning professional. This “hall of fame” made us all dream of our own photographs hanging there one day.

The first thing we all realized when we got to China was that we lacked reading skills. The Academy always placed a big emphasis on solving life & death problems. Each morning started with a one-hour session of problem-solving. Next, we played two games with long time settings: one before and one after lunch. During free time after finishing a game, we were encouraged to review it, study professional games or solve more life & death problems. In fact, we always had material for the latter, with teachers checking our solutions in the morning. We always had a bunch of corrections to make.

After the second game, we had a dinner break, and in the evening a teacher reviewed student games. Mateusz Surma, who was 1-dan professional at the time, advised me to attend the reviews despite the language barrier. As he argued, even without full comprehension of the language, it was still possible to glean valuable insights from the teacher’s demonstrations on the board and expressive speech. Over the course of a few months, I gradually began to pick up some basic words.

CEGO provided us the opportunity to participate in additional Chinese language classes on weekends. Some of the CEGO students embarked on this ambitious pursuit. However, learning Chinese proved a challenge. I remember the first time I could decipher the name of one of my league mates, but when I took a shot at pronouncing it, my classmates started to laugh. Apparently, I had misread the characters 天于 (tiānyú) for similar-looking characters 天子 (tiānzi). Later, I checked in a dictionary and found out that tiānzi translates to “Son of Heaven”, a term historically used to address Chinese emperors.

The CEGO programs start in September and conclude just before Chinese New Year, typically falling in late January. For the period of Chinese New Year, the Academy temporarily closes its doors, and most students return home to their parents. My experience at the Ge Yuhong Academy made me very ambitious and I strived to study more. I asked CEGO if it would be possible for me to return after the New Year break. The sponsors graciously accepted my proposal, and I returned to Beijing in the spring of 2017. I was the only European student at the Academy this time. I really enjoyed the total immersion, and I even began picking up more Chinese. Towards the end of my stay, I was able to have a small conversation with a classmate.

The following year, I couldn’t participate in the complete CEGO program, as my academic leave had finished and I had to go back to university. However, I still applied to attend for the first few weeks. I remember one day in particular from that stay in Beijing when a young girl from Korea joined our school. I played with her in a Small Cycle and had the feeling that she lacked an understanding of the direction of play. However, she was eventually able to turn the board around in one super complicated fight and killed my huge group. Later, I saw her winning most of her games and progressing to higher leagues. The girl was called Kim Eunji. Three years later, she became a professional in South Korea at the age of 13, earning international fame.

In 2018, I joined the program once again. Each CEGO program differed significantly with the European players who joined. Moreover, Beijing was also rapidly changing. Near the school, old restaurants were shuttering their doors while new ones were opening. The Ge Yuhong Academy also constantly adjusted the study schedule. We liked to say that “China is about change”.

A major novelty in the school that year was the introduction of strong computers with graphics cards in one of the classrooms. All students had a chance to study with AI. Moreover, a new feature appeared in the daily schedule: game reviews conducted by a teacher with the aid of AI displayed on a large screen.

In 2019, several youth players attended the program. However, towards the end of that year’s program, COVID-19 reared its ugly head. The European players barely managed to get back home before the borders closed. Over the following three years, travel to China became impossible. Instead, CEGO arranged online training for the European participants. While the online lessons with a Chinese professional were beneficial, the intensity of the training was nowhere near the earlier years.

Throughout the ten-year period of the contract between CEGO and the EGF, over thirty European players joined the CEGO programs. At present, seven of them hold the title of professional player, and it should be mentioned that in this year’s European Grand Slam, twelve out of sixteen participants were former CEGO students.

This summer, I finally managed to visit China again, representing Europe in the MLILY Cup. After the tournament, I traveled to Beijing to take a stroll down memory lane. I went with my fiancée, now wife, who I first met on the CEGO program in 2017. In Beijing we met with Gabriel Wagner, a friend from another CEGO program, who was now undertaking an advanced Chinese language course at the Bejing Language and Culture University. Together, we walked the streets of our old Academy. Everything appeared new, all the restaurants that we used to frequent no longer existed. Nevertheless, we decided to locate the restaurant which we referred to as “the Best Place”, our top choice from 2018. To our surprise, this one was not closed. When we walked in, the restaurant owner immediately recognized us. It felt unbelievable to sit again in that familiar spot and order our favorite dishes.

It was a sentimental journey, and those places will forever remain in my heart. In recent years, the Ge Yuhong Go Academy itself has relocated. The school headquarters is now established in the city of Quzhou, 1,500 kilometers away. However, one week before our trip, we got some happy news: Mr. Ge Yuhong, with utmost dedication, successfully arranged invitations for European students for this year’s study program. As I write this article, the training has already started. Five students from Europe traveled to Quzhou, opening a new chapter in the history of the CEGO program.

Impressions – By Artem Kachanovskyi, EGF 2-dan Professional

I started playing go at a time when personal computers had just started to become common, the internet wasn’t yet popular and mobile phones were just rectangles with plastic buttons. Luckily though, books written by Japanese professional players were available in Ukraine at the time. My favorite were the ones in which a professional commented on his own games, explaining his thought process and sometimes describing the professional tournament atmosphere – I had about five of these and went through each of them several times. The genius found inside these pages magnetized me and I dreamed of becoming a professional go player one day, too.

Fifteen years later, thanks to the EGF and CEGO relationship, the professional system appeared in Europe, and I had the chance to make my dream come true. New opportunities gradually arose in the European go scene, and I have many wonderful memories from go events over the past decade. Let me share some of my impressions with you.

When the EGF announced a professional system in Europe, I was skeptical. The world of professional go in Asia seemed so unreachable that I didn’t believe we could build anything similar in Europe. With that perspective, I didn’t even participate in the first Professional Qualification Tournament in 2014. I was also invited to the CEGO program, but being busy with my education at the Polytechnic University in Kyiv and having just started my job in the IT industry, I wasn’t yet ready to dedicate myself to go.

Meanwhile, other top young European players took the opportunity to train at the Ge Yuhong Academy in China where they significantly improved. As a result of which, I was unable to catch up with them for two years or so.

Pavol Lisý and Ali Jabarin were the first professionals certified by the EGF. My friend and compatriot Andrii Kravets, who participated in the CEGO program along with Pavol and Ali, told me all about how Pavol had won the first Silk Road Tournament in China. Pavol and Ali also participated in the Sankei Cup – a professional tournament in Japan. The opportunities for European professionals seemed serious, and seeing that the first Grand Slam was scheduled for April 2015, I realized that the professional system in Europe was no joke and decided to participate in the second Professional Qualification tournament in Pisa one month before the first Grand Slam. Unfortunately, I didn’t succeed my first time out – the winner was Mateusz Surma. Ilya Shikshin, who had already been a de-facto leader of European go for some time, was the runner-up and also received professional certification. Same as Ali and Pavol, Mateusz attended the CEGO program after he was certified professional.

The Grand Slam was a sensation in the European go scene – there had never been such a high grand prize as that of €10,000. At the first Grand Slam in Berlin in March 2015, I took sixth place after losing to Ali and Pavol. Ilya won the tournament, beating Mateusz in the final.

In 2016 the EGF started organizing the European Professional Championship with attractive prizes and open only to the professional players – a great additional motivation to try to hop on the professional system train that looked to be shaping up. That year, I kept training and won the Professional Qualification Tournament in Baden-Baden, Germany. Andrii Kravets, my lifelong rival, was the runner-up, but that was the year when the EGF started to certify only the winners of the tournament. I was happy when Andrii returned to win the tournament the following year and join the European professional go scene, too.

Needless to say, earning professional player status was a very inspiring event for me. After many years of playing, striving to improve and hard work, my dream came true. Soon after, I took second place in the Grand Slam – another great result.

In autumn that year I traveled to Osaka, Japan to represent Europe in the preliminary stage of the Sankei Cup along with Mateusz Surma 1p. I managed to win three straight games against Japanese professionals, beating legendary Sonoda Yuichi 9p in the third round and qualifying for the main tournament! Even though I lost the first game at this stage and was eliminated from the event, I consider this winning streak as a remarkable achievement for European go.

Let me share with you the background of my go story. I started working as a programmer in 2012, approximately one year before the professional system kicked off in Europe. I was studying in university up until 2015 and spent my vacations at go tournaments. I didn’t have time for a normal vacation like my coworkers, but the more successful I was in tournaments, the more I wanted to live my dream – a life dedicated to go. Due to my passion for go, my performance at work suffered. At some point my boss was fed up and gave me an ultimatum – choose between the two: go or work.

In early spring 2017, after a successful 2016 campaign, I finally made a decision – to leave my job and try to make living as a professional go player. This was a long-awaited step and an enormous weight off my shoulders. About a month later, I won the Grand Slam in Berlin!

That success gave me a lot of confidence. Throughout my career, I managed to win the Grand Slam once more in 2021 and took second place in 2019. For the top players, this tournament is truly a highlight of the calendar, and I sincerely hope that we can have more Grand Slams in the future.

In 2017 – 2019, the European professional team took part in the Chinese C-league – a professional seven-round team competition. Each team consists of four players. I didn’t qualify in 2017, but I was a member of the European team in 2018 and 2019. It was great to dive into the atmosphere of a Chinese professional tournament, review the games together as a team, eat Chinese food and take walks in this new environment. Each year we achieved some feat, surprising the Chinese fans. In 2017 Mateusz won four games out of seven on the fourth board. In 2018 Ilya repeated this success on board one! In 2019 we finally managed to achieve a team victory in one of the rounds. Hopefully, in the future the European team can play in the C-league again and build on our achievements.

Another tournament that takes place in China and has attracted strong European players is the Silk Road Tournament. The level of the Chinese amateurs participating in this event was close to the level of the European professionals and strong amateurs, thus making it an exciting and close struggle. European players have won the Silk Road three times – Pavol Lisý in 2014, Ilya Shikshin in 2016, and myself in 2019. In 2019, the tournament took place in Europe for the first time – near Vienna. Before the eighth and final round, Li Jiaqi 6d was undefeated while I had lost just one game to Ali Jabarin 2p in the fourth. In the final round, I beat Li Jiaqi by half a point. We shared an equal score including tie-breakers (SOS and SODOS). In the end, I brought home the victory to Europe for my first, and so far only, time as I was ahead in the final tie-breaker – mutual games, which means the victor of the game between the two players. That was an unbelievable experience.

I haven’t mentioned yet another great project – the Grand Prix concluded by a Grand Prix Final. Its purpose is to motivate strong players to attend tournaments all over Europe, thus collecting Bonus Points from the 1st of January until the 31st of December in order to qualify for the Grand Prix Final, which happens in the January of the following year. We also used Bonus Points as one of the criteria for nominating Europe’s representative for international professional events. The system worked – for example, at the end of 2019 Ali Jabarin 2p, Pavol Lisý 2p, Mateusz Surma 2p, Ilya Shikshin 3p and I all came to fight for the last Bonus Points at the Hungarian Open in Budapest where, due to relatively low prize money at that time, we normally wouldn’t have shown up.

Although I’ve never won the Grand Prix Final, I have always enjoyed it and took second place in 2018, 2020 and 2021. In January 2020, the tournament took place in Leksand, where Martin Stiassny lives. He invited Andrii Kravets and me to visit his house – all three of us are cat lovers. In his house I noticed a small tunnel in the wall. As Martin explained to me, that’s the best thing in the whole house – the cats can come and go from the house as they please. When I bought my own house later that year, I added a similar tunnel.

In October 2019, the EGF nominated Ilya Shikshin 3p and myself to participate in the MLILY Cup, one of the tournaments considered as a “professional world championship” bringing together some of the best players in the world. While I lost to Xie Ke 7p, Ilya made a sensation by beating Yi Lingtao 7p – a professional from the Chinese A-league and perhaps the strongest player ever defeated by a European in an official game. Observing that game, it was funny to see the other professionals’ facial expressions change when they came and looked at the board – from wondering when Yi Lingtao would finally “finish off this European” to “What is going on here?”.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, bringing with it some tough times – many tournaments were canceled, and we didn’t receive invitations to international professional tournaments anymore. However, I think the EGF managed well and organized many important competitions online, such as the European Championship and Grand Prix Finale. With the Grand Slam, however, we were forced to take a break in 2020.

In the pre-COVID times, all the EGF professionals were able, for some time at least, to live off the winnings of tournaments alone – some for a longer period than others. This way of living is perhaps similar to how the top Asian professionals live – you just train and practice, improving your skills, and then fight against others in a tournament, and so on. Sooner or later each of us came to the realization that a stable source of income was needed, especially after the pandemic set in and big tournaments, such as the Grand Slam, were canceled. For example, Mateusz made his Polgote online go school and is now developing an online platform for connecting go teachers and students, and I make the European Go Journal. Half of the other professionals teach go, and the others work in the IT industry. And since we are in a similar age category, with a difference of just a few years, we have also started families of our own – with women we all met at go tournaments, by the way.

Now the tournament situation has bounced back, but you see fewer of the EGF professionals’ names in the tournament tables. Busy with other things, such as a regular job or a family, we can’t afford to attend as many tournaments as before. That’s somewhat sad, but this is a natural development and I, for example, plan to dedicate more time to training my skills and traveling to tournaments as soon as my kids become more independent and give me more spare time. It’s worth noting that there is still one event that always manages to bring us together – the Grand Slam, due to its high prize money. My greatest hope is that the collaboration between CEGO and EGF can result in at least one more annual event in the Grand Slam series, another tournament like this would be a huge boost to the European go scene!

It’s impossible to compress ten years into one article, but I hope the impressions I’ve shared give you a taste of EGF professional life in the CEGO decade. All these tournaments and wonderful events have attracted the comprehensive attention of go fans from Europe and beyond. The level of the European go has significantly risen – both the professionals and the amateurs were motivated to improve because they were able to witness a brilliant top-level go scene. Besides a few top amateurs at practically the same level and from the same age group as the professionals, I can also see some younger players coming up – for example, my 14-year-old compatriot Vsevolod Ovsiienko 5d who played in the Grand Slam this year.

I believe that a powerful foundation for professional go in Europe has been laid. I am very thankful to CEGO for its support and to the EGF for all its organizational efforts. I am looking forward to a continuation of this story!