What happens to your brain when you play go? Does playing go really affect your brain differently than playing chess does? Most of the statements about the cognitive benefits of playing go are based on hearsay (someone said so) or common sense (of course, mental training improves your mental capacities!).

What happens to your brain when you play go? Does playing go really affect your brain differently than playing chess does? Most of the statements about the cognitive benefits of playing go are based on hearsay (someone said so) or common sense (of course, mental training improves your mental capacities!).Luckily, thanks to the brain imaging techniques used in neuroscience, scientists can now discover what is really happening in our brains when we are playing go. This article introduces some of the most interesting findings to the general audience (the readers interested in more details and specific terminology can access the original studies through Google Scholar, using the references at the end of the article).

What happens to the brain while playing go?

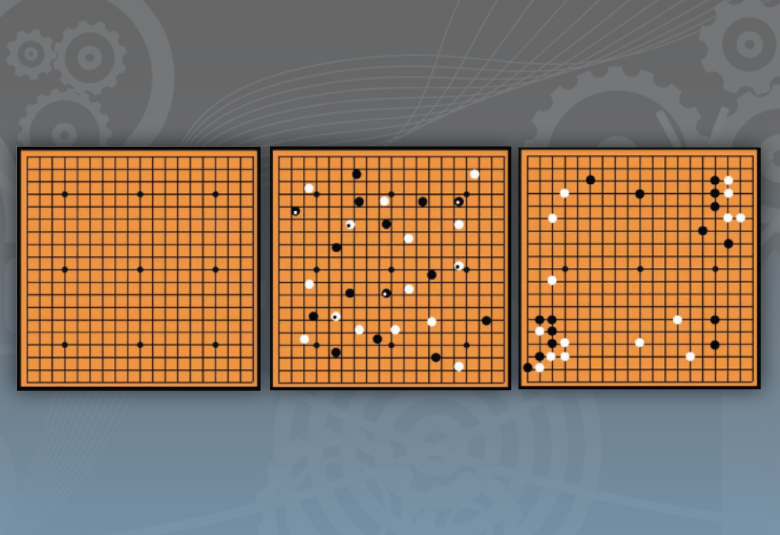

A team of researchers from China and Minnesota (US) studied the effect of playing go in the following way [1]. They presented three different tasks to six right-handed male university students, with strengths ranging from 1k to 1d (non-professional rankings). The tasks, which each had a different visual stimulus, involved:- Staring for 30 seconds at an empty board (fixating task)

- Identifying marked stones on a randomly generated board (visual search task)

- Finding out the best next move on a board with a legal game position (problem-solving task)

While the first two tasks are control tasks, the last one reflects the actual game playing experience. The researchers scanned the brains of the subjects during each of these tasks (using functional magnetic resonance imaging, fMRI) and compared the activated areas of the brain.

This experiment has showed that during playing go (problem-solving task), many brain areas are significantly more active than during staring at an empty go board (fixating task). These areas included the parts of the brain associated with concentration and attention, spatial perception, image manipulation, problem solving and memory processes (working memory storage and episodic memory retrieval). Additionally, the areas responsible for movement were more active, although the tasks did not involve sensory stimuli or bodily movement.

Different than chess?

Go is often compared with chess by people who do not know it that well, and contrasted with chess by those who know both sports. Go players I know eagerly call chess tactical and go strategic; chess complicated while go is complex; and chess local while go is global. If these sports are so different, do they impact our brains in different ways, too?To determine the difference between chess and go, a comparable research study has been performed with chess [1]. This study has found that similar areas were activated during engagement in chess playing. Playing chess has been processed by the brain using spatial mechanisms rather than computational ones.

The only significant difference in brain activation between the two games found by these studies, was the activation of an area associated with language processing during playing go. The researchers explain this activation with the frequent recall of go-related terms by go players during their thinking process. These terms might have referred to parts of basic go concepts, such as tengen (a central point of a go board), semeai (race for liberties between two or more groups) or keima (a knight’s jump).

What about intelligence?

Surprisingly, neither of the two studies showed activation in the areas related to general intelligence. This could suggest that the complex problem solving is performed in other brain areas which are not associated with general intelligence. Another possibility is that the positions used in the experiment did not require much mental effort from the players.Both possible explanations are good news for you, whether you already are a player or only consider starting playing: Either you do not need to be intelligent to solve complex problems (and thus, to excel at chess or go!), or playing those games will make complex problem-solving too easy for the intelligent parts of your brain to even bother…

Now you know this, how about playing a game?

Sources:

[1] Chen, X., Zhang, D., Zhang, X., Li, Z., Meng, X., He, S., & Hu, X. (2003). A functional MRI study of high-level cognition: II. The game of GO. Cognitive Brain Research, 16(1), 32-37.[2] Atherton, M., Zhuang, J., Bart, W. M., Hu, X., & He, S. (2003). A functional MRI study of high-level cognition. I. The game of chess. Cognitive Brain Research, 16(1), 26-31.

Illustrations used are specially made for this article by its author. Always link to the original article if you share or reuse them.